Dr. Douglass Howry was born in Butte, Montana 1920. He received his medical degree from the University of Colorado Medical School in 1947. In the same year he looked into the possibility of applying ultrasound in the production of diagnostically valuable images and consulted with Dr. Carl Spaulding of the California Institute of Technology, and with various other engineers. He became so committed to the idea that he left a formal residency program in radiology for employment with a radiologist in private practice, so that he could devote more time to his ultrasound studies. He subsequently re-joined the training program in radiology under Dr. Charles Ingersoll at the Denver Veterans Administration Hospital. Working at first in his own basement, Howry began investigating the notion that ultrasound beams directed into the body would be reflected from tissue interfaces.

Dr. Douglass Howry was born in Butte, Montana 1920. He received his medical degree from the University of Colorado Medical School in 1947. In the same year he looked into the possibility of applying ultrasound in the production of diagnostically valuable images and consulted with Dr. Carl Spaulding of the California Institute of Technology, and with various other engineers. He became so committed to the idea that he left a formal residency program in radiology for employment with a radiologist in private practice, so that he could devote more time to his ultrasound studies. He subsequently re-joined the training program in radiology under Dr. Charles Ingersoll at the Denver Veterans Administration Hospital. Working at first in his own basement, Howry began investigating the notion that ultrasound beams directed into the body would be reflected from tissue interfaces.

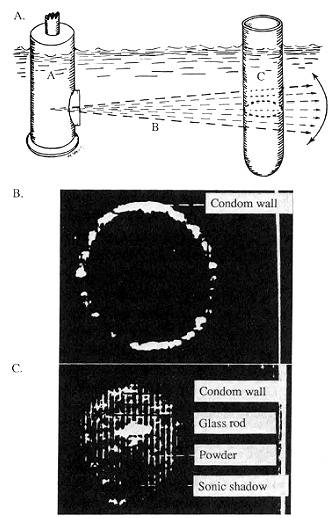

Howry used the reflection technique with pulse-echo ultrasound at frequency of 2 MHz, characteristic of industrial flaw detection equipment. Basing on some preliminary studies, he had discarded the transmission approach. He was chiefly interested in achieving accurate anatomical pictures of soft-tissue structures, rather than the A-mode spikes reported by John Wild at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. Howry was looking for a technique of exteding the scope of radiological practice to inclided the effective imaging of soft tissues. He reported in a later paper "The value of such a system would be greatly enhanced if a true image similar to a roentgenograph or photograph could be obtained, for it would then be possible to visualize normal and pathological soft tissue structures, non-metallic foreign bodies, non-opague gallstones, etc".

Working in collaboration with his wife, Dr. Dorothy Howry and two engineers, Roderick Bliss and Gerald Posakony, Howry produced in his basement in 1949 a pulse-echo ultrasonic scanner. The equipment was constructed from spare parts that were then adapted and integrated to produce a functioning imaging system: electronic parts from radio-surplus stores, a Heathkit oscilloscope, and surplus Air Force radar equipment. A second incarnation successfully recorded echoes from tissue interfaces, and in 1950 using a 35 mm camera Howry recorded his first cross-sectional pictures obtained with ultrasound.

During 1951, Dr. Joseph Holmes became associated with Howry's project. Holmes served as a liaison between Howry and the institutional support needed so badly if the project was to gain financial support and proceed further Holmes functioned as a general administrator and financial planner during those early years. Through Holmes' help, laboratory space for the ultrasound project was found at the Denver Veterans Administration Hospital and a grant was obtained from the Veterans Administration. Under these somewhat more secure conditions the Howry team constructed the most successful to-date of their "home-built" scanners, which incorporated the best of their transducer, amplification, and display systems.

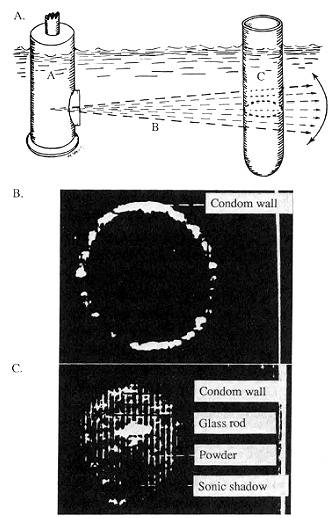

Howry, Posakony and Bliss had introduced multiposition, or compound, scanning to eliminate "false" echoes and produce better images. This incarnation incorporated an immersion tank system using a cattle-watering tank with the ultrasonic transducer mounted on a wooden rail, The transducer, immersed in the tank with the object under study, moved horizontally along the rail. When this equipment produced improved pictures, the Howry team published their results in 1952.

The images, which they called 'somagram' in their 1952 paper in the Journal of Laboratory and Clinical Medicine were probably the most important and inspiring images that were published as pionneering work on ultrasound imaging. A cross-sectional image of a test object, which was a condom filled with fluid and another filled with a water/ talc mixture into which a glass rod had been placed, were demonstrated with sufficiently clarity for evaluation. Images of a forearm with a corresponding anatomical drawing were also shown. These images had demonstrated that utrasound cross-sectional imaging was possible and what needed to be done was to improve on the quality of these images.

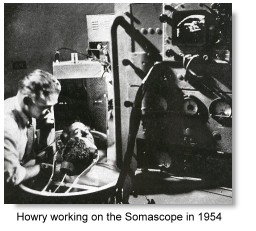

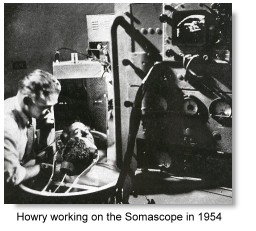

A report on ultrasound images of breast carcinoma was published in 1953. Further improvements led to a more formal version, introduced in 1954, which had the transducer mounted on the rotating ring gear from a B-29 gun turret, which in turn was mounted around the rim of a large metal cup that served as the immersion tank. This permitted complete horizontal circling of the periphery of the tank, while a second motor produced back-and-forth motion as the transducer moved around the tank, resulting in compound scanning of the immersed subject. The innovative apparatus was reported in the Medicine section of the LIFE Magazine® in 1954.At that time, Lithium sulphate monohydride was used as the piezoelectric crystal in the transducer, with much increase in sensitivity. Howry had to grow his own lithium sulphate crystals in the laboratory.

A report on ultrasound images of breast carcinoma was published in 1953. Further improvements led to a more formal version, introduced in 1954, which had the transducer mounted on the rotating ring gear from a B-29 gun turret, which in turn was mounted around the rim of a large metal cup that served as the immersion tank. This permitted complete horizontal circling of the periphery of the tank, while a second motor produced back-and-forth motion as the transducer moved around the tank, resulting in compound scanning of the immersed subject. The innovative apparatus was reported in the Medicine section of the LIFE Magazine® in 1954.At that time, Lithium sulphate monohydride was used as the piezoelectric crystal in the transducer, with much increase in sensitivity. Howry had to grow his own lithium sulphate crystals in the laboratory.

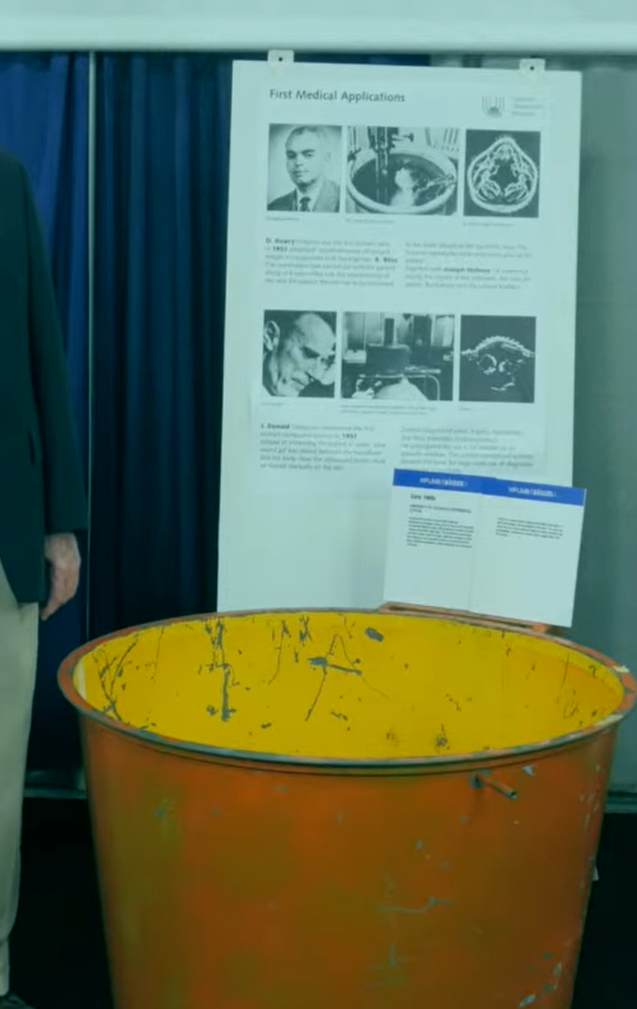

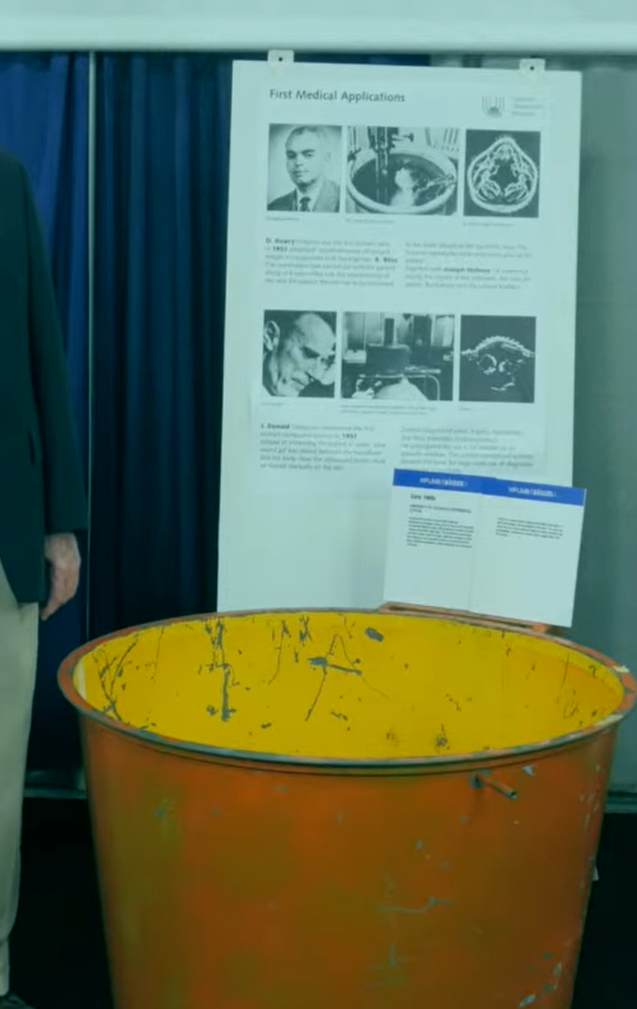

A final version, the pan-scanner, was developed at the University of Colorado Medical Center in the late 1950s under a Public Health Service Grant. This scanner, in which a transducer carriage rotated on a semi-circular water-filled pan that was strapped to the patient's body, was developed specifically to eliminate the need for total immersion of ill patients. The achievement was commended by the American Medical Association in 1958 at their Scientific meeting at San Francisco, and the team's exhibit was awarded a Certificate of Merit by the Association. In the next 3 years the team spent their time improving receiver and display characteristics, acheiving greater consistencies in day-to-day operations. Excelleny studies was obtained on the liver, spleen, kidneys and bladder.

Howry's team recognized the problems inherent in the water-bath coupling system; furthermore, by this time several other investigators, including Wild and Reid and Ian Donaldís group in Glasgow, had published on their work with direct contact scanners. Howry met Donald for the first time in 1960 at an exhibition in London of Donald and Brown's new contact scanners. After he returned to the United States, Howry's group, which at that time had included engineer William Wright, produced a similar device like that of Donald's, and which had quickly evolved into the multi-joint articulated arm scanner.

Douglass Howry subsequently moved to Boston in 1962 where he worked as staff member at the Massachussetts General Hospital. He became a Diplomate of the American Board of Radiology in June of 1967. During the period from 1955 through 1962 he also served as an officer in several small electronic firms including Electro-acoustics Labs., Inc., Automation Industries and Elm-Research Laboratories. He also served as a consultant in ultrasound to many other industrial corporations and government agencies, including Sperry Products, Inc., Westinghouse Co., General Electric, Magnaflux, the Army Medical Service and the National Research Council.

Howry passed away in an untimely death in 1969. The work of Howry and his team, which backdated to 1948, is considered to be the most important pioneering work in B-mode ultrasound imaging and contact scanning in the United States that had been the direct precursor of the kind of ultrasound imaging we have today.

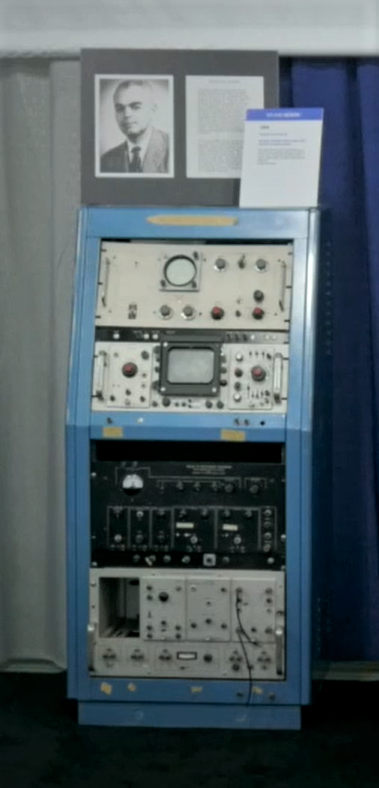

The Howry pan-scanner "tub" and module at an

AIUM historical exhibition in 2016.

Howry and Ian Donald were mentioned as the two most important pioneers.

Read notes and see pictures of the early Howry scanners here, courtesy of Mr. Gerald Posakony.

Read notes and see pictures of the early Howry scanners here, courtesy of Mr. Gerald Posakony.

Read one of the team's earliest articles: The Ultrasonic Visualization of Carcinoma of the breast and othe soft-tissue structures.

Read one of the team's earliest articles: The Ultrasonic Visualization of Carcinoma of the breast and othe soft-tissue structures.

Picture of Dr. Howry courtesy of Mr. Kirk Howry.

Back to History of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology.

Dr. Douglass Howry was born in Butte, Montana 1920. He received his medical degree from the University of Colorado Medical School in 1947. In the same year he looked into the possibility of applying ultrasound in the production of diagnostically valuable images and consulted with Dr. Carl Spaulding of the California Institute of Technology, and with various other engineers. He became so committed to the idea that he left a formal residency program in radiology for employment with a radiologist in private practice, so that he could devote more time to his ultrasound studies. He subsequently re-joined the training program in radiology under Dr. Charles Ingersoll at the Denver Veterans Administration Hospital. Working at first in his own basement, Howry began investigating the notion that ultrasound beams directed into the body would be reflected from tissue interfaces.

Read notes and see pictures of the early Howry scanners

Read notes and see pictures of the early Howry scanners